- Home

- Richard Laymon

A Writer's Tale Page 10

A Writer's Tale Read online

Page 10

The author’s comment may seem like a wisecrack, but it is dead-on accurate.

Learning to write well is probably no easier than learning to remove a kidney or replace a heart valve.

It requires years of study and practice.

Some aspiring writers think they don’t really need to know proper usage of the language.

They think that whatever miserable errors they make will be fixed by an editor.

Wrong.

Most editors (especially here in the U.S.), know less than the writers.

If your story should somehow end up on the desk of a good editor, he isn’t likely to fix the writing for you. The rare, good editor would be so disgusted by your crappy writing that all you’d get is a rejection slip.

Chances are, however, that your manuscript will be read by a lousy editor. Such an editor might accept badly written material simply because he doesn’t know any better.

If that happens, you can be certain that nobody will end up correcting it. The mistakes will be over the heads of the publishers, just as they were over yours. Your book will be published in all its pathetic glory.

Full of mistakes that would win you a flunking grade from any good high school English teacher.

Even if all editors were masters of the language, no writer should ever submit a piece of work that is not written well enough to earn an A+ in any English class in the country.

We have a responsibility to use the language better than anyone else.

A writer submitting a careless, error-inflicted manuscript is like a police officer robbing a bank. It just shouldn’t happen. It should never be tolerated. It’s a perversion of Nature.

This is not to say that liberties cannot be taken. Rules broken. Experiments conducted.

Tricky stuff pulled.

But manipulating the language in order to create special effects is not allowed for people who can’t pass “bonehead” English.

And this is not to say that all mistakes can be avoided. The language is so complex that nobody can get it right all the time.

Mistakes will happen.

They are inevitable. Even if the writer somehow throws together 150,000 words without a single error, the printer is sure to blow it here and there. Errors will slip by.

All the writer can do is try…

Strive for excellence even though it may be unattainable.

Rule 3

“Write.”

The famous science fiction writer, Jerry Pournelle, once told me, “All you’ve got to do is write one page a day. In a year, you have a novel.”

A short novel, at any rate. (By current standards.)

But the point is this… If you want to be a writer, you must sit down and turn out pages.

Even as little as a single page each day can result in a full novel over the course of time.

How long does it take to write a page?

For some writers, a page might be composed in a couple of minutes. (He is more typist than writer.) At the other extreme, a person might spend two or three hours laboring over one page. (Such a person is probably not a great artist. More likely, he’s either a prima dona or doesn’t know what the hell he’s doing likely both.) For most of us, a page might take anywhere from fifteen minutes to half an hour. Maybe a full hour if we’re trying to compose a very special effect or having a problem.

To write a single page per day, then, is a task that should probably take no longer than one hour.

If an aspiring writer is incapable of finding one hour per day to sit down and work on his craft…

Well, let us suggest that he give up the pretense of being an aspiring writer.

Because he ain’t one.

Because anyone can find time to turn out one page a day if he really wants to.

Now, I don’t want to seem like I’m getting hung up in semantics here. A person doesn’t have to write a page every day. Things happen. I don’t write a page every day. I don’t write at all, for instance, when I’m traveling. Now that I’m reasonably successful, I take a day or two off, each week, for activities with my family.

However, I usually do write 100-150 pages per month. That averages out to a lot more than a page per day. My daily goal is five pages. Sometimes I go over, and sometimes I don’t make my five.

Before I was a full-time writer, I held full-time jobs but still managed to turn out a large amount of fiction. (See the Autobiograpical Chronology.) Having a job is no excuse for not writing. My goal in those days was three pages per day.

How did I do it?

Not easily.

I sometimes wrote for an hour before going to work in the morning. I often wrote during my lunch break. I wrote another hour or two each day after work. And I usually devoted large portions of my days off (weekends and holidays) to writing.

I often hear aspiring writers talk about what they are “going to write” if they can ever “find the time.”

With that attitude, they are probably never going to accomplish much.

You don’t find time. It is there. Twenty-four hours of it each day. If you want to be a writer, you only need to make the decision to use at least one of them for the writing.

Turn out that page. Or skip a day, and turn out two or three the next day. But get them done.

Or forget it.

A few helpful hints on how to turn out pages:

1. If you can’t find an uninterrupted hour, it’s hardly worth bothering to get started on real writing. So use the fifteen minutes, half an hour, or whatever to proof-read, revise, or play around with ideas for new stuff.

2. For best results, find a block of two or three hours in which you’ll be able to write without interruption. With this much time, you can get into the piece and really cook.

3. Start each writing period by re-reading what you wrote yesterday. Revise it as you go. This will not only improve yesterday’s material, but it will pull you back into the story, making it easy to continue where you left off.

4. Write the material well, but don’t spend great amounts of time trying to get it “just right.” Don’t spend your whole hour working on one or two sentences. Keep moving. Turn out a page or two or five. Polish them some other time.

5. Follow Hemingway’s advice and stop the day’s writing at a point where you still know what is coming next. This will help you start up again easily the next day.

6. If you are serious about being a writer of fiction, then be wary of foreign entanglements. For example, you might be better off writing your own fiction than trying to edit an anthology or publish a fanzine or run a web site or organize a fan convention, etc. Sure, such activities may gain you some recognition and possibly important connections. But it is more important to make books and stories than contacts. You won’t have any use for the contacts if you don’t have a product to sell them.

Rule 4

“Write Truly.”

The notion of writing fiction “truly” may sound a trifle contradictory.

After all, fiction is made up. How can it be true if it’s made up?

In fact, most fiction is mostly true. You are obliged to be accurate about every detail that isn’t directly related to your story. For instance, such matters as historical, geographical, scientific and technological facts (including how firearms really operate) must be true.

Readers have to be given the straight scoop except when you are manipulating the truth for the sake of the story (in which case, your readers need to be tipped off that you’re bending the truth).

In some cases, novels provide valuable information about fascinating subjects. Most Tom Clancy and Michael Crichton novels, for example, give a lot of insight into one topic or another. Their stories are made up, but their information isn’t.

No matter what you’re writing about, your background material should be as close to the truth as possible.

Which really should go without saying.

But I decided to say it, anyway, on my way to the real subject of my

rule, “Write Truly.”

It’s this.

Everything you write should come out of yourself. Every character, every scene, every story, should be a reflection of you. Pull it out of yourself, not out of movies or television shows you’ve seen, not out of news articles or books you’ve read.

If your stuff is nothing more than a rehash of other people’s work, you’re not accomplishing much. Even if you’re able to make a success of it (which isn’t likely), you’ll be little more than a hack.

To be good, your stuff has to be yours and yours alone.

You accomplish this by writing about what you’ve personally experienced in the real world, not what you’ve experienced vicariously in other people’s books, movies, etc.

For example, suppose you’re eager to write a vampire novel.

Don’t set out to write a book “like Dracula, but different.” Instead, look for a way to make the subject of vampires personal to you. How might your life be affected if you should encounter a vampire? Where might you run into one? How might you, your family, your friends react to the situation?

A hack will do a “mix and match,” creating his stew by throwing together bits and pieces taken from other sources.

A good writer’s novel might also be a stew, but whatever ingredients might be lifted from other sources will be awfully hard to identify and there’ll be a whole new taste due to the author’s secret sauce.

The secret sauce is what makes it good makes it more than just a trite mish-mash of old material.

Pushing this analogy well beyond the boundaries of good sense, I’ll go on to say that the secret sauce is made of the blood, sweat, tears, heartaches and joys of the author’s life.

Every writer’s secret sauce has a different flavor.

Some writers have lousy secret sauce that you just can’t stand. Some don’t even use the stuff at all.

You can tell when it is there and when it isn’t. It’s what makes the difference between a bland story and a rich, spicy one.

It makes the difference between an artificial story and a true one.

Have you ever wondered why you want to read more of certain authors?

‘Cause you like their secret sauce!

But let us now abandon that analogy (a little bit late) and say it straight out: To write truly, you need to tap into yourself as deeply as possible and use what you find there.

Every character, scene, word of dialogue, plot development, etc. is your creation. Allow them to look like your creations.

This is what will make them unique and valuable.

If anyone tells you to write more like Tom Clancy or Mary Higgins Clark or John Grisham, politely tell them, “Thank you very much and go to hell.”

There is only one you, so write like yourself.

It’s what might make your stuff worth reading.

It’s what could make your readers come back for more.

Because, if you do it right, they can’t get the same taste from anyone else.

Rule 5

“Finish.”

Whatever you are working on, get it done.

Just as the world is loaded with aspiring writers who claim they can’t find any time to write, it is also chock full of folks who are busy on a work in progress.” This is usually a terribly wonderful epic novel sure to set the literary world ablaze when the author sets it loose on the public in some unspecified, distant decade.

Yup. Sure.

A work in progress might make for good brag, but it’s otherwise useless.

The artist concentrating on his work in progress and never finishing it is probably afraid it’s no good. And afraid that, if he does get the masterpiece done, he won’t know what to do with himself afterward.

You don’t want to be one of these people.

You want to be a writer. Right?

So do it.

Write the story, write the book. Get it done, send it off, and get started on the next.

In addition to the dangerous WIPS (Work in Progress Syndrome), and somewhat related to it, is the malady that I’ll call LWD (Life’s Work Disorder). Writers suffering from LWD are inclined to stick to a project forever instead of finishing it or abandoning it and moving on to a new project. (It differs from WIPS in that people suffering from Life’s Work Disorder may actually be talented writers seriously trying to create a marvelous book.) They labor year after year on a book, sure that they’ve got a great concept that’ll put them on the literary map or bestseller charts if only they’re eventually able to get it right and/or some agent or editor will finally discover its merits.

Maybe the thing has merits. Or maybe it’s a dud.

The deal is, you might not want to be working on the same book for five, ten or twenty years. If you are devoting that much labor to a book, follow Tom Snyder’s advice and take look in the mirror. You’ll probably see the face of a moron. Or a lunatic.

Here is what to do.

If you have a concept that you think is spectacular, give it your best shot. Do whatever preliminary work might be necessary (research), then write the book. It shouldn’t take you longer than a year if you’re serious. Give it a revision, then send it off, sit down and come up with a new great concept, turn that one into a book, and go on to the next.

Whatever you do, don’t just sit around to wait for the “great book” to get accepted. If it is rejected (which is not exactly unlikely), don’t devote months or years to reworking it in hopes of “getting it right.”

Just put it away. (Maybe go back to it some day, but not now.) Instead of hoping to revive Lazarus, make a baby.

And another, and another.

If you are behaving properly as a writer, you will have a second novel finished before your first novel has had time to find a publisher or accumulate more than a few rejection slips.

At the opposite end of the problem from Work in Progress Syndrome and Life’s Work Disorder is a malady that I will simply dub Quitties.

This is one of the most common disorders, and probably inflicts all writers to some extent.

It happens this way.

You get started on a novel, thinking it is brilliant. You write ten pages or sixty or three hundred then give up on it.

There are a couple common reasons for quitting.

One, you decide the story isn’t working out the way you’d hoped. In other words, it no longer seems overwhelmingly wonderful. So it isn’t worth continuing.

Two, you’ve come up with a new great concept, so you’re compelled to drop the work in progress and start in on the new one immediately.

On occasion, perhaps a work should be abandoned for one or the other of those reasons.

But rarely.

As a general rule, you should resist the urge.

Because, believe it or not, the book you quit writing might have turned out just fine. It might’ve even been better and more successful than the one for which you abandoned it.

But you’ll never know if you don’t finish it.

Your initial enthusiasm for any novel is almost certain to diminish as you get into it.

You’ll have doubts about whether it’s any good at all. You’ll be tempted to give up and try something else. The deal is, it’s natural to feel this way.

And if you do quit and go on to a new novel, guess what pretty soon, you’ll start having your doubts about that one.

You’ll be tempted to stop writing it, too.

If you don’t resist these urges, you’ll end up with a room full of unfinished novels and nothing accomplished.

An unfinished novel is no good to anyone. All it does is take up space.

This is true not only for authors suffering from Quitties, but also for authors trying to sell their work on the basis of a “proposal.”

If you have to submit sample chapters and an outline to your agent or editor, go ahead and do it. But go ahead and do something else while you’re at it: write the book.

Best case scenario: by. the time you

r proposal gets accepted, you’ll have the book ready to send in.

Worst case scenario: your proposal is rejected. But if it does get rejected, you still have a completed manuscript.

An unfinished novel is a waste of space; a finished novel is an asset. Just because a novel is rejected by darn near every publisher on the face of the Earth today doesn’t mean it won’t be bought and published tomorrow.

Rule 6

“Read.”

It should go without saying that writers need to read.

However, I’ve frequently heard authors claim that they don’t have time to read, that they only read non-fiction (research for their fiction), or that they only read books in the genre they hope to conquer.

My “rule” is to read as much as possible across the whole spectrum of published material.

There are several major reasons for this.

First, reading is the best way to learn how to write. Each piece is a sample showing how some other author chose to put words and sentences together, how he described a sunset, developed a character, dealt with dialogue, structured a scene, manipulated a plot.

Basically, everything a person needs to know about writing can be learned by reading other people’s stories, poems, plays, screenplays, novels, etc.

Second, by reading omnivorously, you protect yourself against one of the most common problems encountered by aspiring writers wasting a lot of energy and time trying to write a story that has already been done. If you don’t know the other stories, you’re too ignorant to avoid them. And you really must avoid them. Nobody wants to publish a story that looks as if it’s a remake of an earlier piece by someone else.

If your apparent re-hash does get past your agent and editors and sees the light of print, then you might end up in legal trouble with the author of the original material. And if you’re lucky enough to escape that fate (for instance, if the author is dead), you might end up with a lousy reputation among readers who recognize the similarities and figure you’re a rip-off artist. This can happen even if you’ve never heard of or read the earlier piece.

Third, knowing the other stories not only allows you to avoid them, but to play off them.

HALLOWEEN HUNT

HALLOWEEN HUNT YOUR SECRET ADMIRER

YOUR SECRET ADMIRER TO WAKE THE DEAD

TO WAKE THE DEAD Alarums

Alarums Funland

Funland Cuts

Cuts The Halloween Mouse

The Halloween Mouse The Lake

The Lake Beware

Beware Midnight's Lair

Midnight's Lair Once Upon a Halloween

Once Upon a Halloween The Glory Bus

The Glory Bus The Hearse

The Hearse The Beast House

The Beast House Dreambox Junkies

Dreambox Junkies Night Show

Night Show Dark Mountain

Dark Mountain No Sanctuary

No Sanctuary The Traveling Vampire Show

The Traveling Vampire Show Night in the Lonesome October

Night in the Lonesome October The Woods Are Dark

The Woods Are Dark Blood Games

Blood Games Thin Air

Thin Air Dawson's City

Dawson's City After Midnight

After Midnight A Writer's Tale

A Writer's Tale Savage

Savage Tread Softly

Tread Softly Quake

Quake Fiends SSC

Fiends SSC Cardiac Arrest

Cardiac Arrest Island

Island Allhallow's Eve: (Richard Laymon Horror Classic)

Allhallow's Eve: (Richard Laymon Horror Classic) Friday Night in Beast House

Friday Night in Beast House The Cellar

The Cellar Body Rides

Body Rides The Wilds

The Wilds Out Are the Lights

Out Are the Lights Come Out Tonight

Come Out Tonight Resurrection Dreams

Resurrection Dreams Fiends

Fiends The Cellar bhc-1

The Cellar bhc-1 The Midnight Tour

The Midnight Tour The Beast House bhc-2

The Beast House bhc-2 Endless Night

Endless Night Flesh

Flesh The Complete Beast House Chronicles

The Complete Beast House Chronicles The Midnight Tour bhc-3

The Midnight Tour bhc-3 Beginner's Luck

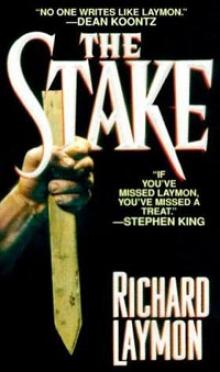

Beginner's Luck The Stake

The Stake