- Home

- Richard Laymon

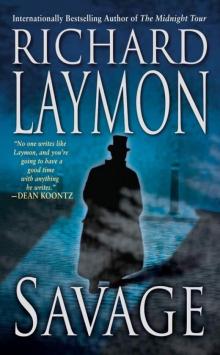

Savage

Savage Read online

Savage

Richard Laymon

LEISURE BOOKS NEW YORK CITY

THIS BOOK IS DEDICATED TO BOB TANNER GENTLEMAN AND SUPER AGENT.

WITH YOUR GUIDANCE AND HELP I’VE GONE BEYOND WHERE I THOUGHT I COULD GO.

—ON TOP OF WHICH—

YOU SUGGESTED AT LUNCH A WHILE BACK THAT I TRY AN ENGLISH SETTING.

SO I DID.

SO THIS BOOK IS YOUR FAULT.

I love my work and want to start again. You will soon hear of me with my funny little games…My knife is nice and sharp. I want to get to work right away if I get a chance. Good luck.

Yours Truly,

Jack the Ripper

—From a letter dated 25 September 1888, attributed to Jack the Ripper

God did not make men equal, Colonel Colt did.

—anonymous Westerner

Table of Contents

Cover

Title Page

Dedication

Epigraph

Prologue

Part One: Off to Whitechapel and on to America

Chapter One The Gentleman, Barnes

Chapter Two I Set Out

Chapter Three Me and the Unfortunates

Chapter Four The Mob

Chapter Five Bloody Murder

Chapter Six I Tail the Fiend

Chapter Seven On the Thames in the True D. Light

Chapter Eight Ropes

Chapter Nine A Rough, Long Night

Chapter Ten Patrick Joins Our Crew

Chapter Eleven Patrick Makes his Play

Chapter Twelve Overboard

Chapter Thirteen High Seas and Low Hopes

Chapter Fourteen Our Last Night on the True D. Light

Chapter Fifteen On My Own

Part Two: The General and His Ladies

Chapter Sixteen The House in the Snow

Chapter Seventeen The General

Chapter Eighteen Forrest Hospitality

Chapter Nineteen The Yacht and the Horse

Chapter Twenty Christmas and After

Chapter Twenty-One Losses

Chapter Twenty-Two Mourning and Night

Chapter Twenty-Three Fine Times

Chapter Twenty-Four Slaughter

Part Three: Bound for Tombstone

Chapter Twenty-Five Westering

Chapter Twenty-Six Briggs

Chapter Twenty-Seven Farewell to the Train and Sarah

Chapter Twenty-Eight Desperados

Chapter Twenty-Nine The Holdup

Chapter Thirty Shooting Lessons

Chapter Thirty-One My First Night in the Outlaw Camp

Chapter Thirty-Two Dire Threats

Chapter Thirty-Three Trouble at Bailey’s Corner

Chapter Thirty-Four The Posse

Part Four: Plugging On

Chapter Thirty-Five Ishmael

Chapter Thirty-Six Strangers on the Trail

Chapter Thirty-Seven Lazarus and the Dead Man

Chapter Thirty-Eight I Get Jumped

Chapter Thirty-Nine Pardners

Chapter Forty The Damsel in Distress

Chapter Forty-One The Gullywasher

Chapter Forty-Two The Body

Chapter Forty-Three I Find Jesse

Chapter Forty-Four Mule

Chapter Forty-Five No Rain, Storms Aplenty

Chapter Forty-Six We Carry On

Part Five: The End of the Trail

Chapter Forty-Seven Tombstone Shy

Chapter Forty-Eight Apache Sam

Chapter Forty-Nine Off to Dogtooth

Chapter Fifty Troubles in Monster Valley

Chapter Fifty-One Ghastly Business

Chapter Fifty-Two Whittle’s Lair

Chapter Fifty-Three The Final Showdown

Chapter Fifty-Four Wounds and Dressings

Chapter Fifty-Five The Downward Trail

Epilogue

Praise

Other Books By

Copyright

PROLOGUE

Wherein I aim to whet Your Appetite for the Tale of my Adventures

London’s East End was rather a dicey place, but that’s where I found myself, a fifteen-year-old youngster with more sand than sense, on the night of 8 November 1888.

That was some twenty years back, so it’s high time I put pen to my story before I commence to forget the particulars, or get snakebit.

It all started because I went off to find my Uncle William and fetch him back so he could deal with Barnes. Uncle was a police constable, you see. He was a mighty tough hombre, to boot. A few words—or licks—from him, and that rascal Barnes wasn’t ever likely to lay another belt on Mother.

So I set out, round about nine, reckoning I’d be back with Uncle in less than an hour.

But it wasn’t in the cards for me to find him.

The way it all played out, I never saw Uncle William again at all, and I wasn’t to set eyes again on my dear Mother for many a year.

Sometimes, you wish you could start from scratch and get a chance to do things differently.

Can’t be done, however.

And maybe that’s for the best.

Why, I used to pine for Mother and miss my chums and wonder considerable about the life I might’ve known if only I hadn’t gone off to Whitechapel that night. I still have my regrets along those lines, but they don’t amount to much any more.

You see, it’s like this.

I ended up in some terrible scrapes, and got my face rubbed in more than a few ungodly horrors, but there were fine times aplenty through it all. I found wonderful adventures and true friends. I found love. And up to now, I haven’t gotten myself killed.

Had some narrow calls.

Run-ins with all manner of ruffians, with mobs and posses after my hide, with Jack the Ripper himself.

But I’m still here to tell the tale.

Which is what I aim to do right now.

With kindest regards from the Author

Trevor Wellington Bentley

Tucson, Arizona 1908

PART ONE

Off to Whitechapel and on to America

CHAPTER ONE

The Gentleman, Barnes

It was a lovely night to be indoors, where I sat all warm and lazy by the fire in our lodgings on Marylebone High Street. I had survived the awful tedium of studying my school lessons (needn’t have bothered with those, really), the servant had gone off to see her sweetheart, and I was perking up considerable with the help of Tom and Huck, who were hatching wild schemes to help Jim escape from Uncle Silas and Aunt Sally. Tom was an exasperating fellow. He never did anything the easy way.

Keen as I was on Mr. Twain’s book, however, I kept an ear open for the sound of footfalls on the stairs. And I kept not hearing any. There was just the sound of rain rapping on the window panes.

Mother should’ve been back some time ago. She’d left directly after supper to give her Thursday night violin lesson to Liz McNaughton, who had but one leg due to a carriage mishap on Lombard Street.

Though it was mean-spirited of me, I found myself wishing Liz had kept her leg and lost an arm. Would’ve put a damper on her violining. That way, Mother would’ve been spared the chore of paying her a visit on such a rough night, and I would’ve been spared my worries.

But worry I did.

I could never rest easy when Mother was away at night. I had no father, nor any but the foggiest memory of him, as he’d been a soldier attached to the Berkshires, and was fetched up dead by a Jezail bullet at the battle of Maiwand when I was just a sprout. Growing up fatherless, I had a morbid dread of losing Mother as well.

So while I wondered what had delayed her return that night, I conjured up a whole passel of dreadful fates queuing up to have a go at her. Even in more normal times, she might have been run d

own by a hansom or attacked by cutthroats, or met some other terrible end. But these were not normal times, what with the Whitechapel murderer lurking about with his knife.

While most of the folks in London knew only what they read in the newspapers, I was quite well versed on all the grim particulars of the Ripper’s atrocities due to Uncle William, who worked out of the Leman Street police station. He had not only gotten a firsthand look at two of the victims right where they fell, but he took a keen delight in regailing me (when Mother wasn’t about) with gory descriptions of what he’d seen. Oh, his eyes merrily flashed with mischief and relish! I’ve no doubt he was quite amused at how I must’ve blanched. However, I was always eager to hear more.

Tonight, awaiting Mother’s return, I wished I knew nothing of the Ripper.

I told myself there was no reason to fear that he might strike her down. After all, one-legged Liz’s flat was no closer to the East End than our own. The Ripper would have to roam far from his usual hunting grounds before coming into our neighborhoods. Besides, it was still too early in the night for him to be out stalking. And he only killed whores.

Mother certainly ought to be safe from him.

But I made my head sore with worrying. By and by, I set the book aside and took to pacing the floor, all in a bother. I’d been at this a while before a door shut down below. That was followed by heavy, staggering footfalls on the stairway. Mother’s step was usually quick and light. Curious, I hurried out and peered down the stairs.

There, struggling beneath the weight of Rolfe Barnes, was Mother.

“Mum!”

“Give us a hand.”

I rushed down and took the other side of the rascal. He was soaked to the bone and stank of rum. Though he hardly seemed able to keep his legs beneath him as we wrestled him up the stairs, he mumbled and growled, deep in his cups.

“We aren’t taking him in, are we now?”

“We most certainly are. Mind your tongue, young man. He might’ve perished in the street.”

And such a shame that would’ve been, I thought. But I held my tongue. Barnes had a habit of turning into a brutish lout after he’d taken a few sips, going foul of mouth and mean of temper. However, he’d fought at my father’s side in the second Afghan war. The way he told it, they’d been great chums to the bitter end. I always reckoned him a liar on that score, but Mother wasn’t about to find fault with the man. From the very start, she’d treated him like a regular member of the family.

Not that she was gone over him. She had the good sense, at least, to reject his amorous advances (so far as I know). Even after declining his marriage proposal some years ago, however, she’d never turned him away from our door.

And tonight, by all appearances, she had dragged him through it.

“Where did you find him?” I asked as we fought our way up the stairs.

“He’d fallen in a heap in front of the Boar’s Head.”

“Ah,” said I. The pub was just at the corner. “He was likely waiting in ambuscade, and fell in his heap when he saw you coming along.”

“Trevor!”

With that, I concentrated on the job at hand.

Barnes grumbled and cursed all the while as we helped him into our flat. Mother responded with murmurs of “Poor fellow” and “You’re soaked through” and “You’ll catch your death for sure” and “What shall we do with you?”

What we did with him was remove his coat and settle him down on the sofa. It fell upon me to remove his sodden boots while Mother took off her own coat, then hurried off to make tea.

I reckon it was her mistake, leaving me alone with him.

My mistake, speaking up.

I spoke up mostly to myself. Muttering, really. I didn’t expect a chap in his condition to hear me, much less comprehend.

What I said was, “Bloody cur.”

Quick as the words left my lips, his fist met my nose and sent me reeling backward. I dropped to the floor. In the next few moments, Barnes proved himself quite lively for a fellow far gone with drink. He bounded over to me, dropped onto my chest, and pounded me nearly senseless before Mother came running to my aid.

“Rolfe!” she shouted.

He clubbed my face once more with his huge fist. Then he tumbled off as Mother tugged his hair. My mind all a fog, I tried to muster the strength to rise. But I could only lie there and watch while Barnes grabbed Mother’s wrist and scurried up. He pulled her to him and struck her face such a blow that it rocked her head sideways and sent spittle flying from her lips. Then he flung her across the room. She fell against an armchair with such force that she rammed it into the wall. On her knees before it, she lifted her head off the cushion and tried to push herself up.

Barnes was already behind her. “Too good for me, is it?” He swatted the back of her head. “You ‘n’ your scurvy whelp!” He smacked her head again and she cowered against the chair, burying her face in her arms.

Barnes clutched the nape of her neck with one hand. With the other, he tore the back off her blouse.

“No!” Mother gasped. “Rolfe! Please! The boy!”

She tried to raise her head, but he cuffed it again. Then he tugged her underthings down to her waist, baring her back entirely.

I was not so stunned by the several blows that I didn’t flush with shame and outrage.

“Stop it!” I yelled, trying to get up.

Ignoring me, Barnes snatched the heavy belt from around his waist. He doubled the leather strap and swung it. With a crack like a gunshot, it lashed my mother’s back. She let out a startled, hurt yelp. Across the creamy skin of her back was a broad, ruddy stripe.

He got in two more licks.

I had tears in my eyes as I swung the fireplace poker with all my strength. The iron rod caught him just above the ear and sent him stumbling sideways, the belt still raised overhead in readiness to strike another blow against Mother. He shouldered a wall, bounced off it, and dropped like a tree.

I pranced around for a bit, kicking him. Then I realized he was knocked out and in no condition to appreciate my efforts, so I figured to finish him off. I straddled him, got a good grip on the poker, and was all set to stove in his skull when a shout stopped me.

“Trevor! No!”

Mother, suddenly standing before me, threw out an arm to ward off the blow.

“Stand back,” I warned.

“Leave him be! See what you’ve done to him!” With that, she fell to her knees at the scoundrel’s head and hunkered over him.

I gazed at her poor back. The thick welts were blurry through my tears. Here and there, trickles of blood made bright red threads along her skin.

“Thank the Lord, you haven’t killed him.”

“I jolly well shall.”

She looked up at me. She said not a word. Nor was a word needed. I hurled the poker from my hand, then stepped away from the still body and wiped my eyes. I sniffed. The sore, wet feel of my nose got me to look down, and I found the front of my shirt soaked with blood. I dragged out a handkerchief to stop my nose from bleeding, then dropped into a chair. I would’ve liked to tip back my head, but I dared not take my eyes off Barnes.

Mother came to me. She stroked my hair. “He hurt you awfully.”

“He whipped you, Mum.”

“It was the liquor, no doubt. He’s not an evil man.”

“Evil enough, I should say. I do wish you’d let me spill his brains.”

“Such talk.” She ruffled my hair in a manner that seemed rather playful. “It comes of reading, no doubt.”

“It comes of watching him whip you.”

“Novels are wonderful things, darling, but you must remember they’re make-believe. It’s an easy matter to dispatch a villain in a story. He isn’t flesh and blood, you see, he’s paper and ink. Spilling a bloke’s brains can be rather a lark. But that’s not life, m’dear. If you killed Rolfe, it would weigh on your soul like a cold, black hand. It would trouble you all your life, keeping you awake at night and torme

nting you every day.”

Well, she spoke in such an earnest, solemn manner that I was suddenly mighty glad she’d stopped me from dispatching Barnes. Though I was sure she’d never killed a person, she knew deep in her heart about the burden of it.

Since that time, I’ve sent many a fellow to Hell. I’ve lost more than a trifle of sleep over it. But the greater burdens on my soul don’t come from those I killed. They come because I didn’t kill some rascals soon enough.

Anyhow, Barnes was still among the breathing. It’d be wrong to polish him off, or so we were both convinced at the time, but I got to worrying about what might befall us if he should wake up.

When her lecture ran down, I got off my chair and said, “We’ve got to do something about him, you know? He’s likely to be at us again.”

“I’m afraid you’re right.”

We both stared at him. So far, he hadn’t stirred. But he was snoring a bit.

“I know just the thing,” I said, and hurried off to my room. I returned a moment later with a pair of steel handcuffs, a Christmas gift from Uncle William who thought I’d make a fine constable one day and wished to whet my appetite for the calling.

Together, Mother and I rolled Barnes over. I brought his hands up behind his back and fastened the bracelets around his wrists.

We stood up and admired our work.

“That should do splendidly,” Mother said.

“Shall I go out and fetch a Bobby?”

Her face darkened. She frowned and shook her head slowly from side to side. “He’d be carted off to gaol for sure.”

“That’s where he ought to be!”

“Oh, I’d rather not have that.”

“Mum! He whipped you! There’s no telling what mischief he’d have done if I hadn’t bashed him. He must be dealt with.”

She was silent for a while. She stroked her cheek a few times. She flinched once, probably due to the sorry state of her back. Finally, she said, “Bill would know what to do.”

I liked the sound of that.

HALLOWEEN HUNT

HALLOWEEN HUNT YOUR SECRET ADMIRER

YOUR SECRET ADMIRER TO WAKE THE DEAD

TO WAKE THE DEAD Alarums

Alarums Funland

Funland Cuts

Cuts The Halloween Mouse

The Halloween Mouse The Lake

The Lake Beware

Beware Midnight's Lair

Midnight's Lair Once Upon a Halloween

Once Upon a Halloween The Glory Bus

The Glory Bus The Hearse

The Hearse The Beast House

The Beast House Dreambox Junkies

Dreambox Junkies Night Show

Night Show Dark Mountain

Dark Mountain No Sanctuary

No Sanctuary The Traveling Vampire Show

The Traveling Vampire Show Night in the Lonesome October

Night in the Lonesome October The Woods Are Dark

The Woods Are Dark Blood Games

Blood Games Thin Air

Thin Air Dawson's City

Dawson's City After Midnight

After Midnight A Writer's Tale

A Writer's Tale Savage

Savage Tread Softly

Tread Softly Quake

Quake Fiends SSC

Fiends SSC Cardiac Arrest

Cardiac Arrest Island

Island Allhallow's Eve: (Richard Laymon Horror Classic)

Allhallow's Eve: (Richard Laymon Horror Classic) Friday Night in Beast House

Friday Night in Beast House The Cellar

The Cellar Body Rides

Body Rides The Wilds

The Wilds Out Are the Lights

Out Are the Lights Come Out Tonight

Come Out Tonight Resurrection Dreams

Resurrection Dreams Fiends

Fiends The Cellar bhc-1

The Cellar bhc-1 The Midnight Tour

The Midnight Tour The Beast House bhc-2

The Beast House bhc-2 Endless Night

Endless Night Flesh

Flesh The Complete Beast House Chronicles

The Complete Beast House Chronicles The Midnight Tour bhc-3

The Midnight Tour bhc-3 Beginner's Luck

Beginner's Luck The Stake

The Stake